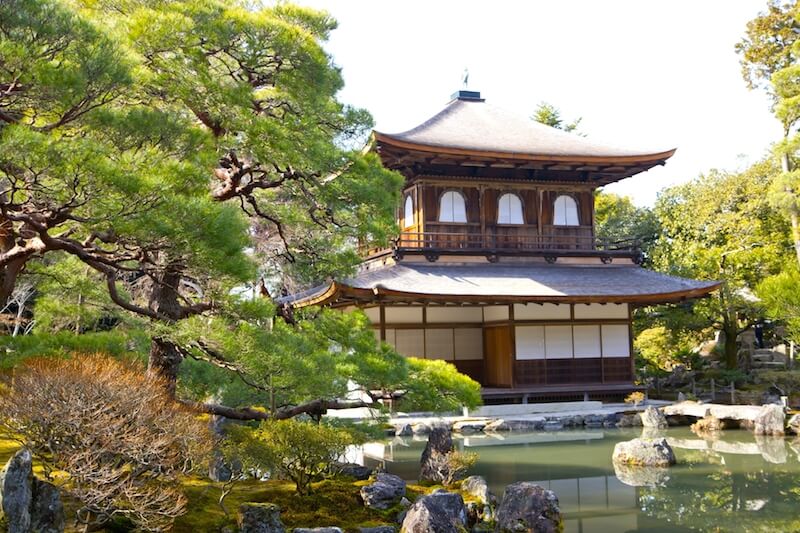

It is a humbling experience when you first encounter an authentic Japanese Zen Garden. Many of the original gardens in Kyoto are over one-thousand years old, dating back to the Japanese Heian Period, when the philosophy of Zen Buddhism was at its intellectual height. These Zen gardens fall within two large categories – sansui (mountain and water) or karesansui (dry garden) styles . Traditionally most people identify the stereotypical Zen garden as the karesansui style, but in fact there are several historically important Zen gardens that have lush greenery, deciduous shade trees, and flowing water features much like our traditional American Gardens – the gardens of Ginkakuji and Saihoji are two such examples.

To many observers, it may seem impossible to recreate the cultural significance and historical character of these traditional gardens; however, there are several ways in which your own backyard can borrow from the ancient Buddhist design philosophy and add your own touch of Zen to the garden. In this article, I will cover three ways that you can add beauty to your backyard while still being authentic to the fundamental principles of the Zen gardening.

Strategy #1: Triadic Stone Placement

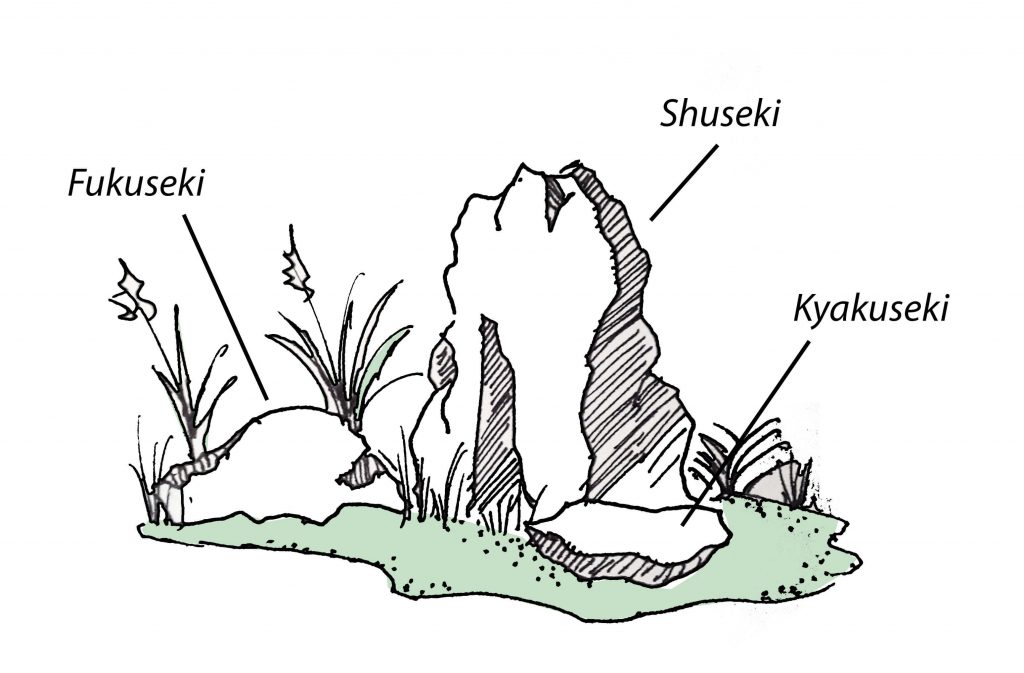

Stones carry a great deal of importance within the Japanese Zen philosophy. They represent a permanence and history within the Japanese culture and are an essential addition to the Zen garden. Most Japanese gardens were designed as reflections of mysterious and natural landscapes that surrounded the capital city of Kyoto. The backdrop of Mt. Hiei and the northern range of mountains that encompassed the city gave historical designers inspiration to work from. Groupings of stones were meant to mimic the wonderful topographical changes they witnessed from afar.

The stones were often placed in a grouping of three – a triad. Zen gardens had specific geomantic rules about the names of the stones and their placement, which can be copied and utilized in your own garden. The dominant stone is shuseki – the initial central stone. It is the focal point of the triadic grouping and should be the tallest of the three. It should be chosen based on its sculptural characteristics. Unique features such as striations, fissures, and markings on the stone are all prized for a shuseki.

The second stone, the fukuseki, should be a short, wide, and squat stone that acts as an anchor of the grouping. The stone should be relatively flat or rounded, without too many undulations or crevices. Unlike the focal stone, the fukuseki is placed to add breadth to the display and complement the height and sculptural quality of the shuseki.

The third stone is the kyakuseki. It is the subordinate of the grouping and is utilized to complete and fill-out the design. The stone should be smaller than the fukuseki in both height and width, ideally being flat and unornamented. If necessary, additional stones may be added similar to the kyakuseki to create a five or seven pair grouping. However, the triadic placement is the most common.

Plants, such as grasses or mosses, can be inter-planted between the stones but are unnecessary – a simple gravel or earthen base is also perfectly acceptable.

Strategy #2: Prayer Card Paths

The pathway that runs through a garden, or around it, is often the last thing that a true horticulturalist cares about; however, for the Japanese designer it is of the utmost importance. The pathway dictates a specific itinerary or journey that the visitor completes. Walking along well planned pathway can provide the passerby with a story of reflection in which small moments of awakening arise. This is keeping with the true Zen Buddhist philosophy.

One design strategy that can be implemented to recreate a meaningful pathway is called the “prayer card path” based on the Japanese Ema, which were small wooden plaques in which Buddhist worshipers would write inscriptions to communicate wishes to unseen spirits. The prayer card path is a reflection of this, using small flat wide stones of various sizes interspersed at specific moments along a pathway.

The entire pathway should not be made in the image of a prayer card, but rather you should identify one or two special moments or views within your garden where you wish people to stop and reflect. It is at these places where you can lay these rectangular flat stones as a means to visually communicate the importance of that location. For the visitor, they will see the notable difference in the pathway, and most likely search for the meaning behind it – a common Zen practice.

Strategy 3: Establish Borrowed Views

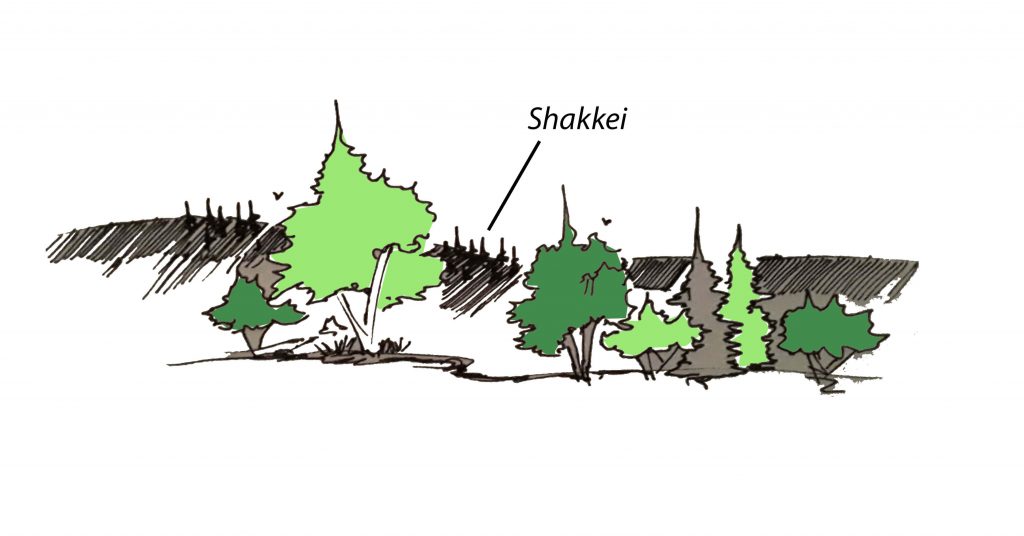

A very common strategy found within Japanese Zen gardens is the shakkei, roughly translating to mean a “borrowed view” or “borrowed scene”. A central tenet of the Zen garden was enclosure. The purpose of the garden was to recreate a miniaturized world in which an idealized landscape is created. Therefore, it was essential to close off and protect the garden by walls or fences. Almost all of the historically significant Zen gardens are enclosed in a similar way, including Ryoanii, Joju-in, and Entsuji.

Although the walls and barriers exist as a means of enclosure, the Zen tradition often identifies key corridors of views to create a sense of promise or awe for the visitor. The corridors, called shakkei, borrow scenery from other areas beyond the confines of the garden itself. In traditional Japanese culture, these borrowed views would be taken from the mountainous landscapes which surround the city of Kyoto, but the principles can still be implemented in your own personal landscape.

One technique is to plant a flowering specimen tree or grouping of desirable shrubs in an area beyond the boundary of your defined garden. Then identify a specific place, or places, within the garden, that is intended to view this feature from. This can be a specific marking along a path, or a dedicated bench or stone. The intention is to highlight the created view from within the garden, even though the beauty lies beyond it. You can also combine this with the triadic stone grouping – in which the grouping can designate the location to view from, or be located beyond the garden as an element to view.

As you can see, there are several small changes you can make in your existing garden or yard to add the flair of a traditional Zen planting. The history, culture, and philosophy of Zen gardens is unique and complex, with a multitude of variations and styles a gardener can borrow from.

If you are interested in learning more about techniques and strategies for adding Japanese Garden elements to your gardens, please check out The New Zen Garden: Japanese Design Principles for the Residential Landscape.

____________________________________

Important Legal Disclaimer: This site is owned and operated by Draftscapes. We are a participant in affiliate marketing programs designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by linking to participant vendors. Affiliations include Utrecht Art Supply and Amazon Associates. Draftscapes is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. Recommendations for products or services on this site are not influenced through the affiliation.